The Royal Canal in Ireland was a white elephant. It had been built by an over-zealous entrepreneur who intended it to compete against the nearby Grand Canal, but it went disastrously over-budget and he was nearly broke by the time it was completed. Then the railway came to Ireland and didn’t so much eat into his prospective profits as devour them. He was finished. He would have been better off wasting his money on building a tunnel to America, rather than ‘borrowing’ his neighbour’s idea, and so he fell flat on his arse. The canal just sat there for decades, forgotten about, gradually declining, falling into disrepair, and mostly unused except for some localised traffic. Old barges sat in the shallows, rotting, often their skeletal remains being the only reminder to a lost industrial past. A section near my childhood home was clear as crystal, with no boat traffic to churn up the mud. There the canal was easily thirty feet wide, five feet deep and ran 21 miles between locks. In my younger days we’d cycle along looking for shoals of fish, then dismount and harass them. We saw massive shoals of bream, huge rudd everywhere, the occasional tench, and lots of long, mean pike.

In 1994 this ignored and dilapidated canal breached its banks and a JCB had come to the rescue and blocked the water from emptying fully out into the fields, but it had taken at least a day to stem the flow. So the injured canal simmered through a hot summer about a foot lower than it would normally be. Whether it was the higher-than-normal water temperature, or some other, as yet unseen factor, I’ll never know, but for some reason the fish were enthusiastic in their appreciation of a well-presented bait, and we caught well.

By then, my own fishing journey had taken me far, in terms of improvement of skill, but only just down the road in terms of location. My fishing buddy Peter and I explored every inch of this section of canal, before reaching an out-of-the-way stretch near Mullingar, called the Downs. I say out-of-the-way in that hardly anybody went there. It was between two towns, and people didn’t stop to look around. But it was good farming land, bountiful and green, flanked by bogs, and easy enough to access, as you simply drove the car to your swim and parked in a hedge and fished.

Peter and I came to the Downs in his little Suzuki Alto, stuffed to the gills with fishing gear. He was an enthusiastic purchaser of new tackle, and any fishing trip started with a visit to a tackle shop in Dublin (coincidently also on the banks of the Royal Canal) where they’d roll out the red carpet whenever they saw Peter walking in the door. Peter was a professional poker player, so a fishing trip invariably followed a win at the poker table. Under those circumstances, understandably, being financially prudent wasn’t really on the agenda for my flush friend. The guy behind the counter would tot up the bill in his head before knocking off a suitably rewarding percentage as a loyalty discount, and throw in a pint or two of maggots for good measure. We were always sure they closed the shop straight away and headed for the pub after our visits.

On the bank we met a Swedish gent who fished a long pole across the water, catching fish after fish near the far bank, which was flanked by a rising field of corn. Against the reflection you could see the fish passing through the swim, and often staying to be fooled by his bait. The Swedish chap told us “Ze tench are everyvar. Ze tak ze red maggotz, zometimes ze sveetcorn. Early morningzar bezt. I fish unteeel midday, zen I go bakzu Dublin. I do ziz every Zaturday, like ze clockwork.”

With spinning rods in hand, we walked and fished a fair bit of the canal either side of our Swedish friend. When we returned he was gone. 12.05 was the time. Just like clockwork, as promised.

I was within shouting distance of Peter when I heard a mighty crash and looked around to see the surface of the canal in turmoil, with Peter effing and blinding to the four winds. When I reached him he was just staring at the water, the dissipating ripples from a massive fish bobbing at his feet. He had hooked the biggest pike he’d ever seen. We patrolled the area looking for her, and a few casts further down I found her, skulking in a hole behind a fallen branch. She was enormous, the biggest pike I’d ever seen too—still to this day—but she knew we were there and ultimately we tired of harassing her, and left her alone.

We continued to explore, and that evening we settled into a swim further up the canal, where it widened to allow barges—that didn’t exist—to turn around. We figured we would fish the Swede’s swim at first light, as with limited time on the water we should explore our options. In the darkening evening sky we caught a lot of rudd, then Peter caught one that was easily two pounds, in almost total darkness. We had forgotten our float lights, so we’d moved around the swim to a spot where we could see the float in the reflected light from a nearby farm. That beautiful fish led him on a merry dance before revealing its golden flank in the light of our torches.

The great thing about sleeping in cars, ignoring the distinct lack of comfort, is that the morning chorus of birdsong always wakes you up, and there’s never any need for an alarm. This time, however, it was the sound of heavy breathing that did it. I was in a semi-dream state and was aware of the sound before my eyes would work, and I thought that either some monster was still in my head, or Peter was having an interesting dream. “Thank heavens the gear stick was in the way,” I thought. Instead it was a cow from a neighboring field that had stuck its own head through a gap in the hedge and was licking the windscreen. Mooooooorning? Excuse the pun.

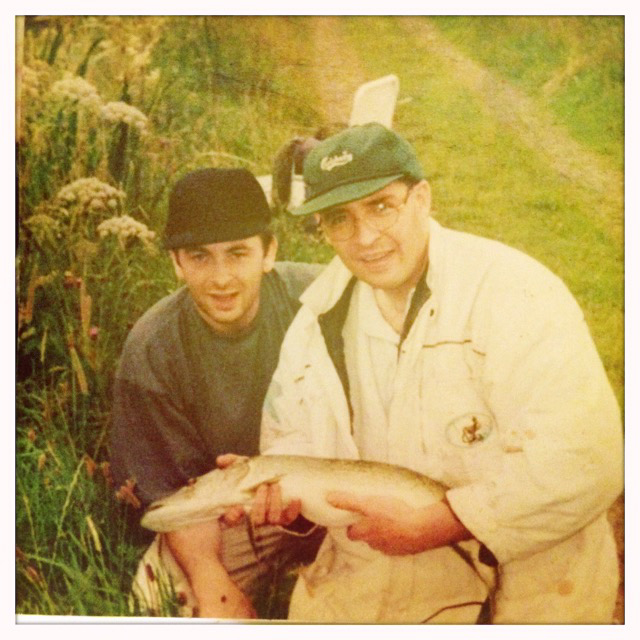

Tossing a coin for the Swede’s swim, I lost and fished about 10 yards to the left. There were no features, so I got the swim rake from the car and carved a thin line of weedless ground about 15 feet out, and resolved to fish at the tip of it. Lightly groundbaited, and fed with a steady stream of maggots from a catapult, within 30 minutes the swim was fizzing with bubbles. I adore tench bubbles. Their eating habits are so refined, careful, delicate. They are so polite as to make their presence known to you before they fully enter our world, like knocking before they come into the room. and as I followed the trail of surfacing gas I could see them getting closer and closer to the tip of the float. A few nudges, some gentle bobbing, given some time, and down the float went. What followed was a ferocious battle on light line, with the tench burrowing deep in the weeds. I’d gain control only for her to set off again, this way and that, several times down into the muddy bottom of the canal. But eventually up she came, for it was a female, the gentle, smooth lines of her fins having that feminity that is missing from those of the more robust and angular male. And what a lovely shade of olive green she was, all four pounds of her.

We caught a few tench that morning, perhaps eight or ten, and over that summer we fished the very same spot again and again, and we watched it develop into one of the best tench swims I have ever fished. On one particular evening, fishing again with Peter, but while also tutoring a friend of his from Germany, we caught 26 tench in the last four hours of the evening, with 14 falling to my own rod. We had stopped using keepnets by then, so it’s possible we caught the same fish more than once, but as an indication of the head of fish in that stretch it was nothing short of remarkable.

There were other remarkable things about that stretch. Carp were not common on the canal, but a very few were there. Soon enough they found their way under my float tip. There were a pair of them, each slightly under ten pounds. We never caught them, but I certainly hooked them. You could see them swimming into view, and their larger bubbling marked their path, and you knew you were in trouble. No matter what we tried I just couldn’t manage to get the hooks to stick, and they’d either break the line or the hook hold would fail. But it added to the excitement.

Other species had their kings too. Royal Canal perch are never very big, in my experience, but there was an enormous perch in that stretch that was surely all of four pounds. That’s a bit like looking into a goldfish bowl and finding a fat carp, or peeking into the pool of a high burn, and seeing not a small trout, but a salmon. That perch remained a ghostly presence. When you went looking for it, you could never find it, but when you were least expecting it, there it would be, smack bang in front of you. We have all had those moments when your eyes are trained on the distant float, but something moves in the margins, under you feet, and catches your eye. That was the domain of that giant perch. And no matter what we tried, we couldn’t catch it.

The big pike showed herself too, snatching at the odd rudd on its way to our net. We’d always know when she was in our swim as the bites would stop like the flicking of an underwater switch. On other occasions the small fish would suddenly scatter in front of a giant bow wave as she drove through a shoal. But she ignored our lures, and we were too inexperienced to think our way around the problem of catching her, and too focused on catching tench, or at least I was. Peter had developed nothing short of an obsession with that fish for three weeks, thinking of little else, even when he was at the poker table, and it was beginning to effect his work, but strangely not in a negative way. His focus on work had moved from playing 6 days a week, to only playing 3 days a week, to allow him to fish more with me. For whatever reason this galvanised him, and he became much more successful at the table, and he’s carried this principal forward to this day, allowing him enough time to fish, enough time away from the poker table, to clear his thoughts, and to enjoy himself. I’ve often thought I can learn from him in this regard. So roughly every Thursday or Friday we’d jump into his little car and hit the road, heading for the Downs.

Peter would have his foot to the floor, pushing the Suzuki Alto to its maximum to get down to that stretch, and when he’d arrive he’d frantically trail his lures up and down in search of her. When I discovered the art of dead baiting we were filled with excitement, and Peter has goosebumps at the very thought of what was to come. When we got to the swim the first thing we did was put an oily sprat under a pike float, and we cast it next to a big bed of weed. There was so much adrenaline that it was difficult to get our fingers to work, and we stank of fish. But in the sprat went and we got on with the task of baiting up the tench rods. Before we even had the lines through the rings of the rod, the pike float went under, and Peter nearly tripped over himself to strike into what we were sure was the matriarch. He shouted what has since become his trademark “Woohoo!!” as he bent the rod into the fish. Surely all his dreams of mammoth pike were about to come true? Whatever it was got lodged in the reed bed, and we couldn’t feel its true weight for a few minutes until it broke free. But the subsequent pike was a mere four or five pounds, not thirty. We were disappointed, confused. It didn’t make any sense, as we’d never seen or hooked so much as a jack when the matriarch pike was around. Then the next morning, right on cue, Anders, the Swede arrived:

“Ze big pike was caught last week. It weighed 31 poundz. Ze boy who caught it cut off ze head with a shovel and threw ze body on za bank. I found it zat day and buried it. “ He, and we, were gutted.

Peter was inconsolable: “When we discovered her death at the hands of that 12 year old boy, a deep, deep anger rose within me at the actions of this uneducated brute. That anger is still there, for he took away my obsession, just like that”.

The death of that pike signalled the death of that stretch, and within a year we went in search of pastures new. But it sowed the seeds for the quest to catch big pike, and tench, further afield in Ireland. There were smaller pike all over that stretch by then, with no enormous matriarch to prevent them from cutting into her territory. Shoals of little roach now proliferated, and the tench stopped biting, or had simply moved on. Walks along the bank never revealed wandering tench anymore, whereas before you could always spot them, like little zeppelins, floating along aimlessly. Other anglers too had found the spot, but we knew we’d had the best of it. And as for the perch? It was never seen again.

I often think how this place may have only existed because people had forgotten about it, and as a result, it had found its own way, its ecosystem perfectly in balance, leading to some truly amazing fishing, until a foolish young lad, who knew no better, killed a trophy fish.

But the foolish industrialist who sank his last pennies into that canal can rest easy, as his legacy is still intact. The water is healthy, the canal renovated and taken care off, and fish are present. If left alone and to its own devices, who knows? Maybe there’s another 30 pounder waiting for Peter right now?