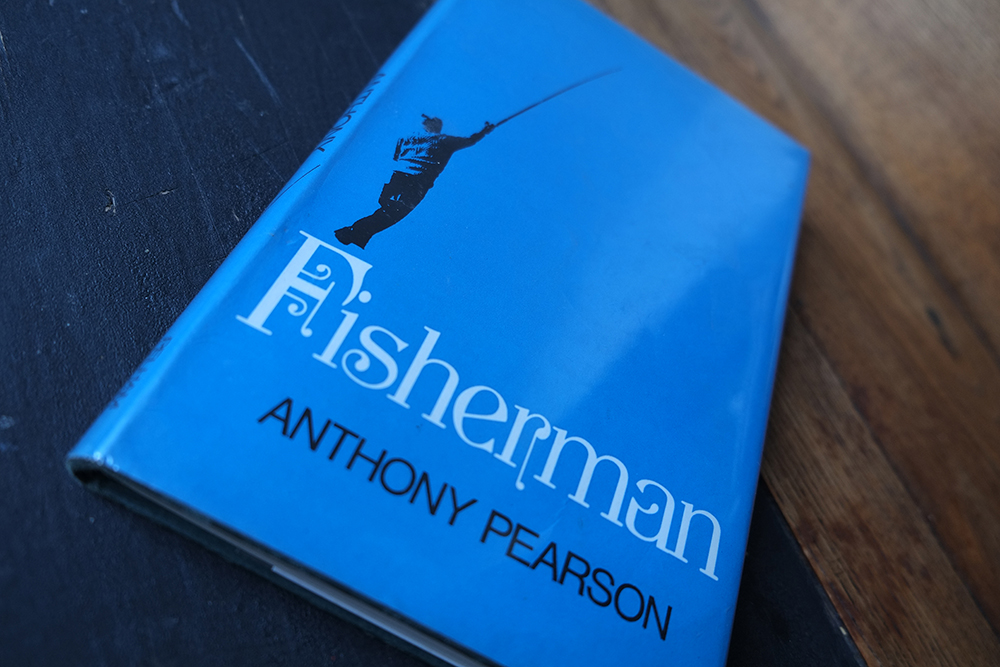

It is the Congo in 1960. A man called Jack Allan dies after being strafed across the chest by machine gun fire. Pearson grips us immediately; guns, mercenaries, Africa, elephant hunting, hard drinking bound together by the thread of fishing, especially for billfish—sailfish, swordfish and marlin—the harsh but thrilling environment of a restless man with ice in his veins and a storyteller at heart, who wished only to live life the way he wanted, beholden to nobody, free.

“I… seemed to spend my whole life running away from enclosures whether they were fences, ideas, communities or rules. I was in love with the wild notion of freedom even though it was a selfish one and involved only myself. ”

Pearson was a Lancashire lad who caught his first fish—a chub—from the river Wyre, before becoming a talented all-round angler under the guidance of his father, equally adept at spinning for pike or match fishing for roach as he was at beach casting for bass or cod.

After school he lived in Kenya, becoming firm friends with its chief fisheries officer, Major Douglas Smith. Exotic fish came to his rod, once even under the watchful gaze of a leopard. This is real Boy’s Own stuff.

It is easy to lose oneself in his childhood adventures, especially pike fishing, and his love of the coastline in Co Kerry in Ireland resonates strongly with me, but it is Africa that really gripped, the tales the giant marlin and the dangerous “pingusi” (shark) that were hauled to his boat.

“Once you have Africa inside you it is impossible to shake off. It is with you forever.”

Place names like Muthaiga, Kikuyuland and Kilifi punctuate the pages with exotic imagery. His occasional use of Swahili places him firmly under a hot sun where the cold beers in the bar afterwards must have tasted all the sweeter.

Pearson continually uses the Swahili word “bahati”. It translates roughly as “luck”, but it means more than that, an acknowledgement that fortune favours the brave perhaps, that one has to earn it, and he does.

I can’t help but feel there is an undercurrent of conflict that makes me wonder what was going on inside his head; something perhaps self-destructive or, on the other hand, enlightened? Is his isolation to be pitied, or envied? He writes beautifully, but doesn’t mince his words; often terse, writing it as he sees it, his vernacular straightforward and functional but laden with subtleties. It has strong echoes of Hemingway, some of Zane Grey, but there is a sensitivity beneath it that is alluring. He talks of a female flamenco dancer with a passion that is, well, stirring. I wonder is there regret somewhere in his heart, or is his tone a reflection of hardships he has seen with his own two eyes, the death of a friend in his arms, his sadness at killing an elephant.

That is the beauty of this book. Its accounts of smaller fish are wonderfully evocative, and of bigger fish intensely gripping, but it is the man who muscles his way through it all that I find most interesting. Do they make men like that any more? Do people live those kind of lives? I do not know. I have tried to find out more about him, what happened next, when he died, did he ever marry, have a family? Perhaps it doesn’t matter. It was the life of a fisherman. Brilliantly written. It is as simple as that.

Review by Garrett Fallon