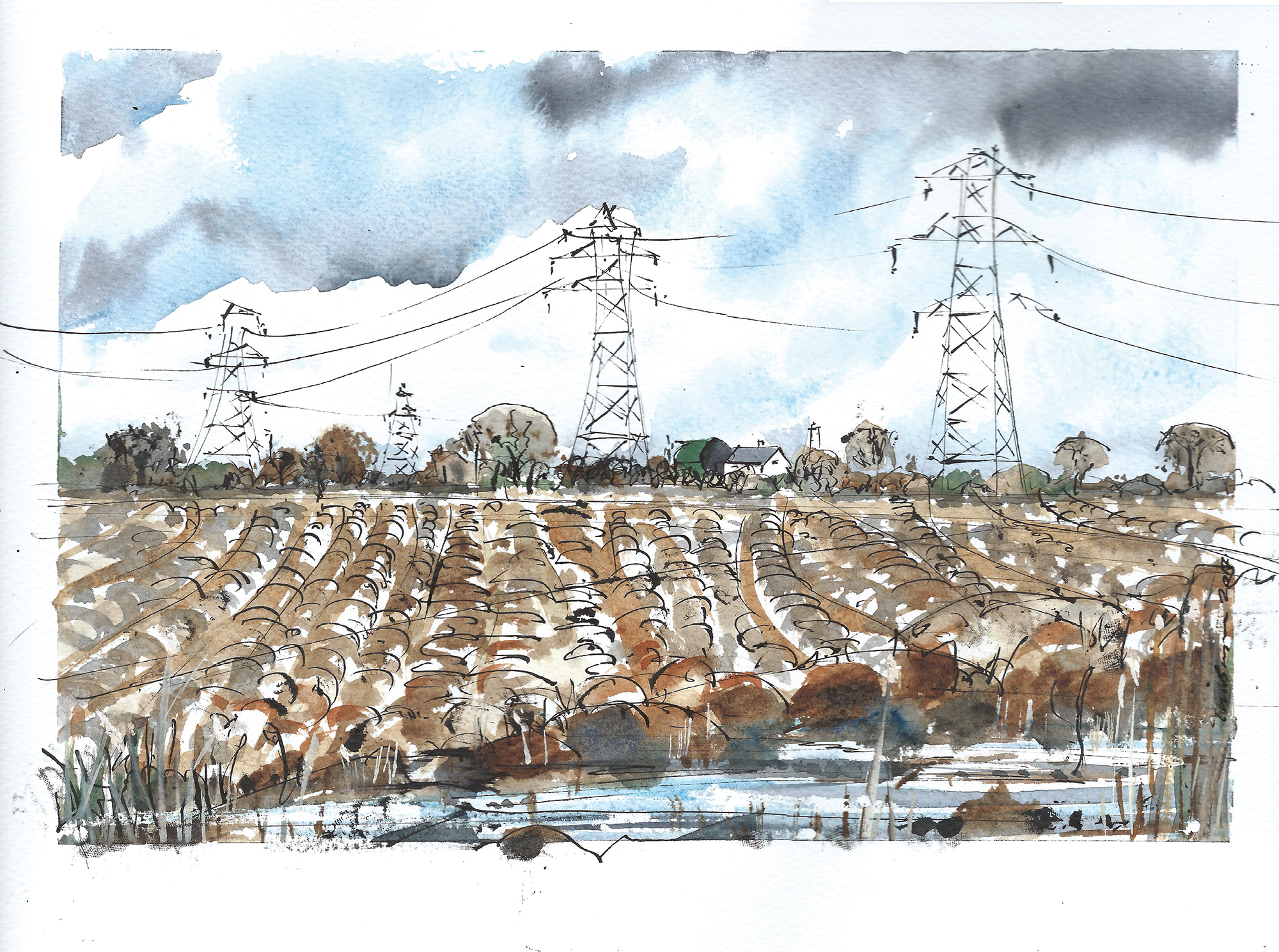

In the car, he thinks about time, and how much there used to be. How, years ago, playing an LP was a thing in itself. You lowered the stylus, there was that amplified crackle, and then you sat on the bedroom floor, playing every track before turning the disc with a deft flip of the fingers and listening to the other side. Those long, white-skied days. Bowie on the turntable, morning drifting into afternoon. And outside, the raw fields, the sweeping winds, the pylons and puddled lanes. Fishing was something you did because, for a teenager, it was the only mystery that the place had to offer.

They drive on. They left early to beat the traffic. He hoped to talk, to have one of those conversations that can happen on a car journey when there’s just the two of you. Instead, for two hours now, there’s just been the whisper of headphones. I’m here, his son’s attitude proclaims, but here on sufferance. Don’t make too much of it.

The village is not much changed. The cheerless pub, the row of shops that always seemed to be shut, the supermarket that was once a Spar and is now a Londis. He parks, takes out the rods, and shoulders the tackle bag. In the playing fields the old swing has been replaced with a climbing frame; he can hear, to this day, the unoiled squeak of that swing. How many roll-ups did he smoke there? How many Kestrel lager cans did he chuck at those wire-framed bins?

The river looks much the same. The brambles are denser, and shreds of old plastic bag flutter from the overhanging branches, but the current is high and strong. As he puts the rods up, and his son checks his phone yet again, he wonders if this was a good idea. When he himself was 16, and living in the village, boredom was a fact of life, like acne and Stork margarine and Songs of Praise. It bred the kind of frustration that could get you into trouble, but also patience, and an angler’s stoicism.

His son, forever online, never quite present, has yet to experience that sort of boredom. Fishing might be just too slow a game for him. If he doesn’t catch, always a probability on the river, it will merely confirm to him the pointlessness of this and all such dad-inspired ventures. They make their way upstream. His son is dressed in a T-shirt printed with the words ‘Bad Porn’, and a flimsy zip-up jacket. Instead of wellingtons, he’s wearing scuffed and unlaced construction boots. He looks cold, but the impracticality of the outfit is the point. A mute protest against the tyranny of the sensible.

They pass a bend in the river where the current undercuts the bank, scouring out a deep hole beneath spreading willow roots. Decades ago he hooked a big chub here, and it nosed into the roots and broke him. It’s always haunted him, that fish. He should have turned it with side-strain, and finished the fight in open water. Easy to be wise after the event, of course. They continue upstream, every step a memory. Back then, he used to fish in an old US Army M65 combat jacket bought in a surplus store. What happened to that jacket? Disappeared, like so much else from that time.

At the top of the stretch he lowers the gear. Watches as his son slings his worm-baited hook into the current and animates it with desultory jerks of the rod. After 10 minutes of this the boy reels in, glances listlessly at his phone, and wanders off downstream. His father fishes the swim more carefully. The river’s as dark as well-hopped beer, and he explores every swirling eddy and wind-ruffled slack. After an hour without a touch, however, he begins to wonder if there are any fish there at all. Have they been poisoned by chemical run-off from local agri-businesses? Eaten by cormorants? Netted and sold by poachers? Or have they, like his M65 jacket, just vanished into the past? You thought, when you were young, that you would always remain so. That you had all the time in the world, and that things would stay the same. And then, like an Aerial reel unchecked, the years started flying by. Racing unstoppably towards some unknown break point.

Taking up his rod, bag and net, he goes in search of the boy. They’re supposed to be fishing together, after all. Unhurriedly, he retraces his steps, peering into the river’s obscure depths. Fly-tippers, he sees, have been active on the far bank. There’s a gashed mattress, its yellow foam innards spilling out, and several refuse sacks of builders’ waste. And then, where the river bends, there is his son. Not mooching around, benumbed and resentful, but bending into a big fish, his rod hooped into a quivering arc.

The battle plays out. The fish is holding deep, revealing itself in a series of dim flashes. The rod kicks hard, but gradually and inexorably a huge chub is brought into shallow water, netted, and lifted onto the bank. For a moment, father and son gaze in silence, marvelling at the blunt head, the amber-ringed eye and the shining pewter flank. “Wish we’d brought a camera,” he says, and his son smiles. “The phone, Dad…” When the fish has been carried back to the river, and has vanished with a flick of its broad grey tail, they look at each other. “So how did it all happen?” his father asks. “Tell me.”

“That guy showed me. Told me to cast under the bank, so that the worm was carried under the tree roots. He said that if I got a fish on, I should bully him out fast, so he couldn’t snag me.”

“I didn’t see anyone.”

“You must have. He went round that corner just a second before you appeared. Young bloke, in a US Army jacket. Looked familiar.”

“Ah,” says his father. “Him.”

Words by Luke Jennings

Illustrations by Tim Baynes

Originally published in Fallon’s angler Issue 9