This is the first of over twenty short stories about life in Ireland by Niall Fallon, who died suddenly in the 1990s, before anybody had seen them. They have remained hidden from public eye, but no more.

PADDY MURPHY WAS A LOCK-KEEPER ON THE GRAND CANAL. He lived alone, in the small, compact cottage set beside the lock gates; it was a pattern which repeated itself a score or more times along the wavering length of the canal. There was the cottage, whitewashed, neat hedges well-trimmed, a path of swept gravel, and a byre at the back for a cow, a shed for a few hens. In front of the house, a few feet away, the great lock gates stood, all heavy-barred oak and cast-iron fastenings, the two enormous handles askew on either side; beyond that ran the River Barrow, broad and swirling by the low bottom meadows. And behind all sloped the broad side of Mount Brandon with its corduroy stripes of plantation.

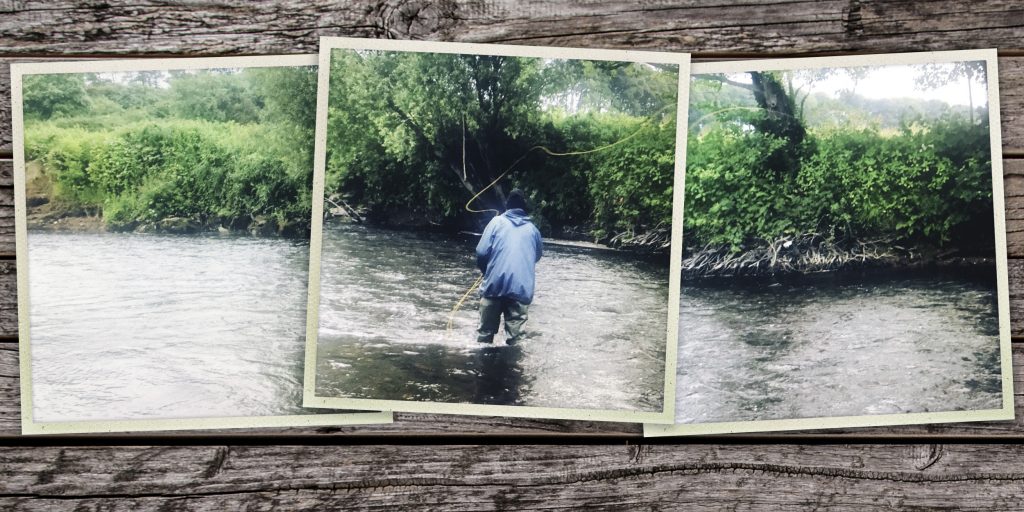

It was a quiet place. It had always been so, more or less, even in the days when traffic on the canal flowed much more densely. Now there was only the odd pleasure craft venturing through the weedy stretches; it was an event when one idled slowly up to the gates and its owner clambered up the rickety ladder to inquire at Paddy’s door. Paddy was always there. He had little else to do, in fact, except perhaps to set his long line in the river, surreptitiously at dusk, when no-one was around. Nearly always he could guarantee a trout or perhaps an eel, and sometimes even a salmon, for his line was so strong as to hold a young whale if the occasion ever arose. He shot sometimes in the thick woods crawling up the mountain’s slope, bringing back the odd pigeon and sometimes an out-of-season pheasant.

Beyond that, he lived simply, rising at sunrise, retiring at dusk after the long line had been baited. He was a small, squat man, neatly built, with good shoulders and tireless legs; he had a small, greyed head, all grizzled stubble, scalp and eyebrows, grey as a badger.

I first met him when I was fishing. I had come down from the village steadily casting across the broad slow reaches of the river until I reached the weir. It was a hot sultry August afternoon and the fish were asleep for I had got no touch on my fly. The weir looked more promising, a long diagonal cut across the river, the smooth deep water above it running into the canal and below it the rough rippling runs down a long glide to where Paddy’s cottage nestled snugly under the hillside. I crossed the canal in a little punt I found in the reeds, hoping that no-one would find me out and, if they did, that they wouldn’t mind my using their boat.

As I had hoped, the water on the other side was promising. The weir had caused a split here i between the canal and the river, the lower end of the weir running into a narrow island which ran all the way to the lock gates. I cast across the rough water and in a second there was a snatch at the fly and I had a good grilse on. He gave me trouble too, and I was hard pressed with the weight of water to bring him to heel. But in a few minutes the net was under the silver body and he was flopping on the rough stones at my feet. As I took the fly out of his mouth, I looked up and there was Paddy.

He was standing at the top of the bank, looking curiously down at me. He said nothing and his blue eyes were unwinking. A collie dog stood at his feet.

I stood up and smiled at him.

“Nice day,” I said.

He nodded his grey head slowly.

“Tis,” he answered.

I gestured to a point beyond his back. “I hope you don’t mind me using your boat,” I said. “I thought I might get a salmon here and it was the only way I could get across.”

I gestured to a point beyond his back. “I hope you don’t mind me using your boat,” I said. “I thought I might get a salmon here and it was the only way I could get across.”

Paddy clambered down the bank. “Use away,” he said. “Divil the use that boat gets at the best of times. I never use it meself, except when I want to get across the oul river.”

He came closer, his eyes on the grilse at my feet. “That’s a nice fish”, he ventured cautiously. His eyes glanced at me warily. I sensed rather than felt the question.

“You’re not the bailiff?” I said.

He laughed. “Deed an’ I’m not. I thought you were him for wan minnit.” He lowered his voice and glanced around. “That man is a divil, Sir, and if you haven’t a licence, you’d be better off out of here, for he’s a holy terror if he catches you on the wather.”

“Oh, I have a licence” I said, “and permission from the riparian owners to fish this water. But I’m not doing well so far.”

“Oh, god,” said Paddy, “an’ you’re doin’ well enough.”

What he said was true enough; the grilse was a nice fish, firm-fleshed and chunky, shining silver from the sea whence it had come perhaps two days before. I looked across the river.

“This is a good spot?” I asked Paddy.

“Tis, but ‘tis not many you’ll get this day, with the sun; too bright. Maybe this evenin’ when ‘tis cooler you’ll get wan or two.”

I offered him a cigarette, which he accepted with alacrity and we lit up. I put my rod aside, somewhat reluctantly, for I did not wholly believe what Paddy had said about not getting fish. I had only been there for five minutes and had concrete evidence to prove that the day was not that unsuitable for my small grilse fly. But then, I had borrowed his boat and the least I could do in return was to be courteous.

We got to talking about fish and the fishing and Paddy introduced himself as the owner-tenant of the cottage downstream. He told me, sotto voce, and with many glances around him, that the bailiff was his great enemy and had accused Paddy of poaching his preserves. “An’ all I ever did,” Paddy told me indignantly, the light of battle in his eye, “was to take a salmon or two when I was hungry and you couldn’t try a man for that.”

While I could see Paddy’s point, at the same time I could understand the bailiff’s natural anger with him. He was a born poacher. What, for instance was he doing on this little spit of an island where no-one ever went except perhaps to fish? I asked him.

“There’s two sheep down the way there and I’m getting’ them out a that,” he said. But I could see, just peeping from the pocket of his torn grey jacket, a loop of line.

“Nice spot for a long line”. I pointed, casually, to a spot some twenty yards downstream, where the water slowed and deepened in under our bank. Seatrout and salmon might lie in such a spot; eels there must have been plenty. But what had prompted my query was not the likely spot but a thin wisp of silver coming from behind a cluster of flags to enter the river a few feet out—a nylon line.

Paddy had me weighed up long since. He looked at me now. “Aye, ’tis a good spot. I have a bit of a line out there meself a few minnits but I don’t think there’s anything doing. I’ll look at it now” and with the words he was on his feet. I followed him down as he handlined the line in, armed with three hooks and baited with bunches of worms. There were two eels, each about a foot long. Paddy had his supper caught.

Paddy had me weighed up long since. He looked at me now. “Aye, ’tis a good spot. I have a bit of a line out there meself a few minnits but I don’t think there’s anything doing. I’ll look at it now” and with the words he was on his feet. I followed him down as he handlined the line in, armed with three hooks and baited with bunches of worms. There were two eels, each about a foot long. Paddy had his supper caught.

“I’ll be off now, Sir,” he said. “The best of luck to you and don’t mind the bailiff.” I said goodbye and he disappeared with a last wave over the bank. Presently two sheep broke from a clump of hazels and Paddy appeared again, driving them before him. I returned to my fishing.

All that long, slow afternoon I fished solidly down that stretch, searching thoroughly every inch of water that might hold a fish. But of fish I saw none and the gilt had gone off the river’s earlier promise. I had no rise and by six o’ clock had little further hope of one. But I could now sit down by the lock gates and eat my sandwiches; later on, when the sun went down and the brightness went from the water, the fish would wake up and the grilse might take. I had plenty of time; I would wait and see if I could add another to the solitary fish in my bag.

I was sitting with my back against one of the arms of the gates, dozy with sandwiches and sun, content to wait for the evening rise, when a voice from behind startled me into sudden wakefulness. I turned, coming to my feet. A few yards away stood a small wizened man, with a thin, weasel face, top-booted and carrying a rod. He was, I guessed instantly, the bailiff.

“Good evening,” I said affably.

“Got a licence?” The words were curt, officious, ignoring my greeting. I fished in my pocket for my licence and handed it to him. He read every word, turning it closely in his mind, then handed it back.

“Let me see your bag.” I was under no obligation to do this, but the officious self-righteousness of this little man had not quite melted away the mild spell which the warm evening sunlight had cast on me. I opened the bag.

“There’s only one in it,” I said, handing it to him. As he took it, it struck me, suddenly, that the bag was very heavy. This fact evidently had entered his mind also, for as he took the bag from me, he cast me a glance of disbelief. He produced one grilse, two, three… three fat, fleshy, silver, solid fish lay in the grass at his feet. I stared at them incredulously. His sharp eyes were on me.

“One was it you said? Or can’t you count? The good fairy is looking after you today alright!”

His tone so angered me that I recovered my senses rapidly enough to answer him.

“One good one was what I meant”, I said, turning over the largest with the toe of my boot. The largest was several pounds heavier than my own catch. Suspicion and astonishment had been succeeded in my mind by inner laughter. It must have shown on my face for the bailiff said, abruptly, ”are you quite sure you caught all them fish yourself?” He cast a quizzical eye on the sun, still bright on the swirling water beyond the lock.

“I’ve been an hour along beneath here and devil the fish did I see, let alone catch.”

“Perhaps that good fairy you mentioned was looking after me,” I ventured. “Or maybe you’ve got the wrong fly on.” I was enjoying his discomfort.

Footsteps sounded on the gravelled walk that ran from the gates down to Paddy’s cottage and Paddy strolled out his gate to join us. He touched his cap deferentially to the bailiff, who answered it with a glare, and then his gaze caught the three fish on the grass. He whistled in astonishment.

“Begod, and that’s a great catch”, he said, admiration in his voice. “ You must have a great bit of fly there sir, to catch all them. And Mr Byrne here and not a fish in his bag. Well, well, well… ”

“Begod, and that’s a great catch”, he said, admiration in his voice. “ You must have a great bit of fly there sir, to catch all them. And Mr Byrne here and not a fish in his bag. Well, well, well… ”

The bailiff swung on me. “You caught all these?” he demanded.

“They were in my bag,” I said, “so I must have.”

Paddy’s wide grin and half-suppressed mirth must have brought a hint of a smile to my face, for the bailiff’s face darkened in anger. He hesitated, shifting his furied gaze from Paddy’s face to mine and back again. Mirth, I think now, was by this stage writ large on both. Suddenly, he whirled on me.

“You think you have me fooled, don’t you?” he snarled. “Well, I’ll be watching you from now on. Don’t think you’re all that smart.”

He turned abruptly on his heel and stalked down the path, his large waders flapping ludicrously around his skinny legs.

I looked at Paddy. His face was serene, untroubled by the scene he had witnessed. A slight anger rose in me at the thought of future embarrassment which might befall me at the hands of the riparian owners of this water and also, I must confess, at the way in which I had been used to take a rise out of the bailiff.

“That was a nice trick,” I said severely.

His clear blue eyes met mine innocently. “Sure, what would I do and me with two fine salmon in me hands and I seen him down the river watchin’ me cottage for to see if I was takin’ his salmon? Sure, you wouldn’t mind; I knew you’re a good man to take a joke.”

There was little I could do except to laugh and to agree with him. After all, there was, in fact, very little that the bailiff could do to my future chances on the river and Paddy’s feelings about that worthy had taken root in me. I ruefully bent down, gave Paddy his two grilse, hefting the solid fish lovingly in my hands, wished him good evening and set off down the river bank.

The sun had gone down and the light had softened. The river ran quietly and invitingly, and here and there trout rose with the soft “plop” of a big one to a fly. The grilse might take soon.

I started fishing.

*****************

Postscript: It is important to remember that this story was written at some point in the 1970s, when the attitude to killing salmon for the pot was very different to what it is today. Fallon’s Angler in no way condones the killing of salmon under any circumstances.

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between.

(Thanks to subscriber ‘Phil” for this suggestion).