Words and photography by Stuart Harris

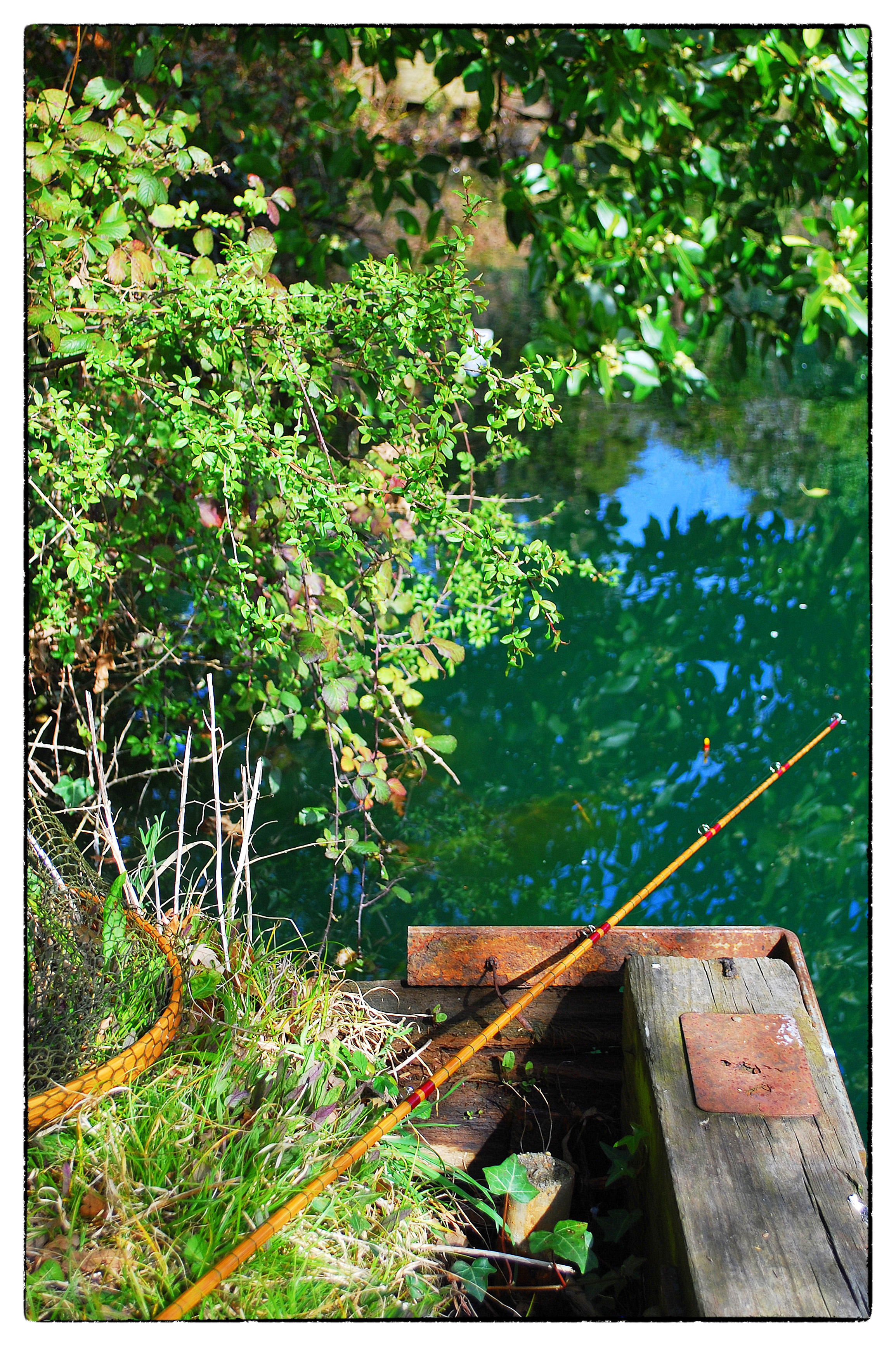

It was the sudden flash of blue that brought me back to earth and out of my daydream. It happens a lot you see, lazy, hazy spring days where the sun’s rays warm my shoulders, I slip out of reality and into a faraway land where nothing matters and time gathers like basking carp in the shallow corner of a sun-dappled pool. A kingfisher zips past and the float I’d been watching for most of the morning comes back into view. It was just in the nick of time too, the float swayed to the left quite aggressively as if something of considerable size had brushed past the line. The water beneath me was cloudy, I squinted looking harder, and caught sight of the culprit. Certainly not a bream, no forked tail, the dorsal was in the wrong place and besides, the bream aren’t a foot wide in here.

It can be a frustrating business, float fishing for big carp in slightly deeper water. Such bulky fish, with large paddles sticking out all over the place, there’s always something to catch hold of the mainline and cause the float to spin, dance and even shoot under leaving me wondering just when is the right time to strike. The last thing you want to do is foul-hook the fish, you need to be sure the hook is in its mouth, and with all the silt and debris swirling around the swim, you just cannot see. The ideal scenario is when the carp moves along the shallower marginal shelf and spots your hook-bait sitting naturally on the lake bed, stoops down, extends those lips and picks it up, there is no mistaking then. Call me picky, but I have been known to tweak the bait at that point in favour of hooking something more desirable.

There have been times when I’ve politely asked my ten-to-the-dozen heartbeat to tone it down a tad, for fear of the carp hearing it and scarpering before I get the chance to strike. It’s an incredible feeling when you hook a monster at close quarters. For a split second or two it just holds fast, assesses the situation whilst contemplating its next move. Its eyes swivel in their sockets as it looks around, probably weighing up which way to bolt, which is usually in the direction of the snags. This is their domain, and they know exactly what to do next.

Then the fun begins, that first powerful thrust, that dash for freedom is quite exhilarating. I don’t believe anything that swims, pound for pound, has that same power. As much as you prepare yourself for that initial first run, you’re never quite ready for in, and by no means in control. Line leaves the reel, the rod hoops and there’s not a great deal you can do but hold on and hope you manage to avoid the underwater obstacles and that the hook stays in. Usually after that first bid to escape, you can begin to gain back some line, resume some sort of control. A tug of war ensues with something angry, it doesn’t like you or want to meet you and will try everything in the book to ensure it gets nowhere near that net you’re just about to reach for.

There are two ways this can go too, you can be victorious which, for the angler, is always the most favourable conclusion, or you can fail to bring your prize to the bank. The latter has a twist too, and mostly it depends on whether or not at some point throughout the fight you caught a glimpse of what it was you were attached to. You may have seen it early on—perhaps you were fortunate enough to watch it pick up the bait in the edge—in which case you’ll know exactly what you just lost. Maybe you didn’t, maybe you have no idea what just evaded capture, the fish of a lifetime, the carp you’ve chased for eternity, with no way of knowing whether it might just have been the one. Either way, time heals and soon after your next momentous capture you’ll have forgotten the loss, or at least it won’t hurt as much when you think back.

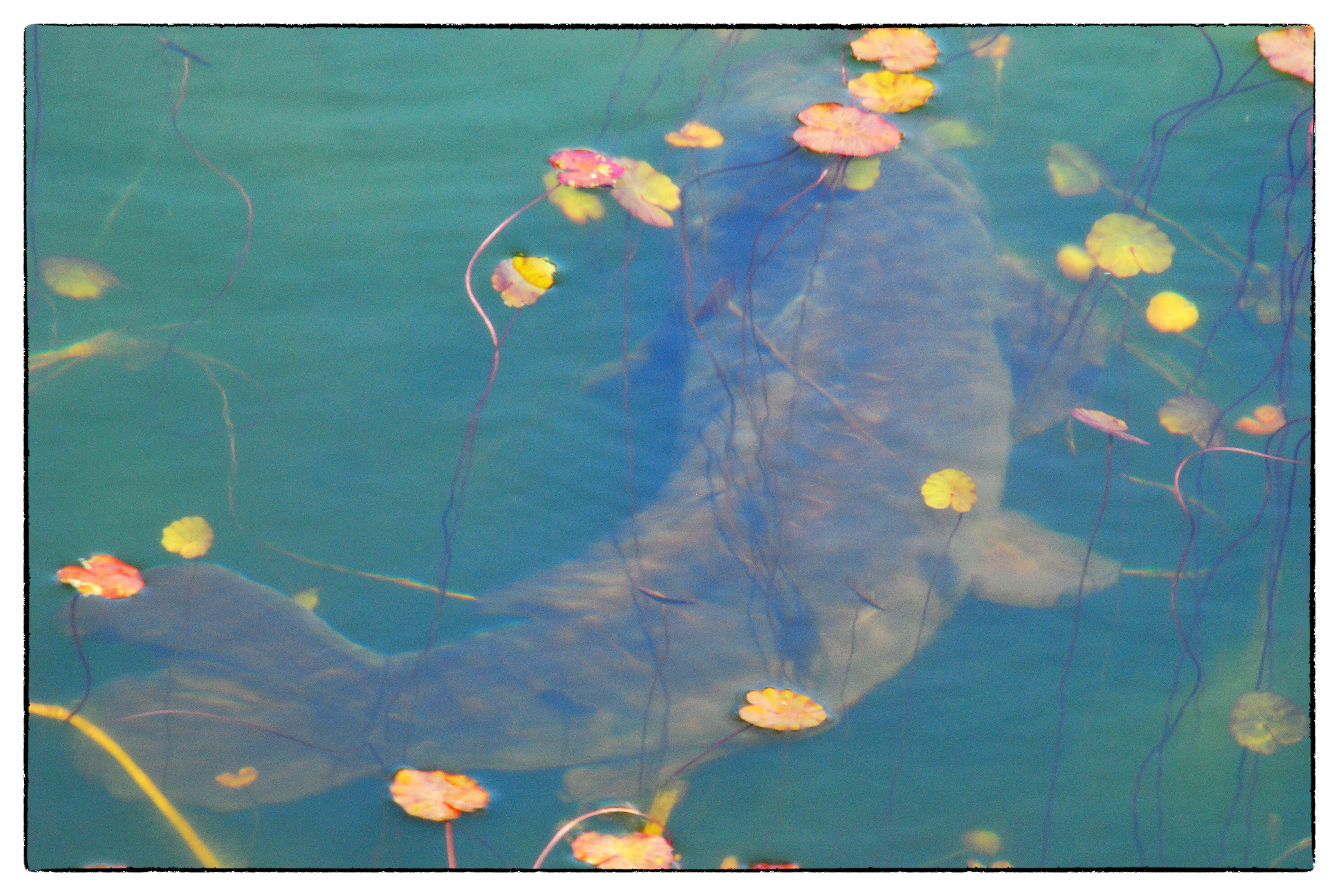

So back to the day in question, the carp I could just about make out through the agitated silty water was a good one, easily over 25lbs, but I just couldn’t quite ascertain whether it was a common or a mirror. Then, just as quickly as it had appeared, I could no longer see that dark shape beneath my float. The cloud settled and the water cleared, and there, resting on the bottom, were my two bright yellow grains of sweetcorn, the ones with my size ten hook pierced through them. All the others were gone, every piece eaten. How do they do that?